When my dad sat down to write his most recent book about Darwin, he did so with over a dozen written volumes so thick that they would have been as tall as me if you'd stacked them up. This was primary source material -- which might surprise you, because maybe you know that Darwin didn't publish that may actual books in his lifetime. But they weren't published books at all: these were the seemingly endless troves of Darwin's many obsessively-kept letters. There are 19 published volumes as of today; more are promised to come as the task of transcribing Darwin's correspondence continues to be an undertaking. (If you're curious -- and who can blame you -- most of this stuff is readily available online.)

We learn a lot about the great thinkers of the modern age by reading their letters. Benjamin Franklin's have been famously transcribed and used to help further modern scientific discoveries. Rilke's are requisite reading for any Composition 101 class. Ernest Hemingway's earliest letters -- written before anyone thought of him as a genius, in a personal era of unsurpassed hope and surprising machismo -- reveal a version of himself no one would have guessed had ever existed. There are, in fact, countless collections of letters made famous on the backs of their more famous writers. Reading them is a bit like discovering a tiny secret. Sometimes when there is no supposed wide audience to pander to, some very interesting truths emerge.

I think letters are more fascinating to read than journals. They reveal more than just details about their writers: they tell stories of relationships and chart their growth or lack thereof. I spent a whole day last summer reading John Steinbeck's letters in the Steinbeck library in Salinas, and couldn't put them down. The collection diagrams all three of Steinbeck's marriages; from the courting stage ("If you are in love — that’s a good thing — that’s about the best thing that can happen to anyone. Don’t let anyone make it small or light to you"), to the polite exchanges that occur after a great love has ended, where friendship feels forced but imperative. ("Strange. I have a feeling that everything has stopped and is waiting -- rather like some Sunday afternoons or the hour before a party. [...] I guess that's all for now. I must write to the boys.") You can witness his tone change as he writes to an ex-wife in one moment, to a girl he likes in another, to a business associate in the next, to one of his sons later. A collection of letters shines a bright light on what we do to love; how we form relationships and what we feel is necessary to maintain them.

***

The first time I wrote an e-mail I was in seventh grade. I was in a classroom that had once been a home economics room, and it still had the 1970s-orange ironing boards and a string of sinks that once prepared young girls for their inevitable Mad Men-style futures. Now the classroom was a "technology" room, manned by a squat, balding former gym teacher named Mr. Emig, who knew very little about technology. The room had two rows of cumbersome HP computers, each with big, gray keyboards and black mouses with comically long cords. One day, we departed from our normal routine of going through the motions of "Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing" for an hour before a ten minute free time (during which everyone used AltaVista to search for Backstreet Boys gossip). Mr. Emig told us the school had outfitted all of us with e-mail addresses, and that our assignment that day was to send an e-mail to someone else in the class.

I sent my e-mail to Jacob Camperelli, who was sitting right next to me. I asked him what his three favorite foods were. In five minutes, I had a reply: Pizza, chicken wings, and brownies. I remember knowing, even then, that my world was going to get turned upside down.

E-mail changed everything. I had always liked writing a lot more than I liked talking to people. When I was trying to get someone to be my friend, I liked to send her letters in the mail or pass her notes between classes -- long, winding diatribes about cute boys or books I'd read. I did not receive many responses to my forced epistolaries, but that didn't stop me from trying.

Now I had this vehicle to write to anyone and everyone at school, and the novelty of sitting at a computer to correspond brought the reply rate up tenfold at least. In just a few months, I'd have a desktop in the basement of my own home, and a few months after that, I'd be using AOL Instant Messenger to write messages to people all over town, all at once. Maybe everyone from my generation has a story like this, but for me, it was too good to be true. Suddenly, introverted communication was readily socially acceptable, and seemingly overnight I went from being a relative outcast to having scads of virtual friends who thought I was funny and smart.

In college I met this cute boy named Alan Wexmen in the section lounge, and knew immediately I wanted to date him. Like second nature, I hopped over to my computer and threw together a two-parts-witty-three-parts-snarky-one-part-unapologetically-firty little e-mail to him. He wrote back within a few hours. Before I knew it, Alan and I were writing to each other every day -- although we lived just three doors down from each other on the same dorm floor. We told each other crazy secrets and waxed poetic about philosophical ideas, all in virtual type. Within three weeks, we were making out in the section lounge.

Our love didn't last, but our friendship did. We kept writing e-mails throughout all four years of college. They continued to be intimate and funny; strange and winding. When I got a note from Alan, I'd stop whatever I was doing and read it three times in a row. There was a deep and beautiful ritual to all of it. When I read Steinbeck's letters all the way through last summer, I was immediately reminded of the lilt and timbre of Alan's e-mails. You find a rhythm when you correspond enough.

Then we graduated from college. In September, the registrar sent an e-mail to everyone in our graduating class telling us to get our affairs in order, because at the end of the month our school e-mail addresses -- and all the data attached to them -- would be erased. And just like that, this beautiful, protracted correspondence disappeared forever into the ether.

***

I fell in love with another boy via e-mail as an adult. We wrote e-mails to each other every single day, without exception, for two years. About a year in, I panicked. When I tried to search our correspondence, Gmail told me that there were "hundreds" of messages containing his e-mail address; meanwhile, the little bar telling me how much digital space I had left to keep files in my account was slowly filling up. I spent six hours copy and pasting every e-mail we'd ever sent into a Word Document, and had it all bound in a book. The boy liked it -- he even listed it as one of the 18 things he'd keep if his house was burning down.

Herein lies one great loss we are collectively experiencing, and we don't even think about it most of the time. We are living in an age where we are no longer able to preserve our correspondence.

This is why I insist on writing letters. I write them because I want there to be something for my grandchildren to find in the attic. I write them because I want to remember that I was in love, or that I fell out of love, or that my heart felt so broken once, but it healed. I write them to preserve this very private, relational part of my own complicated, typical human story.

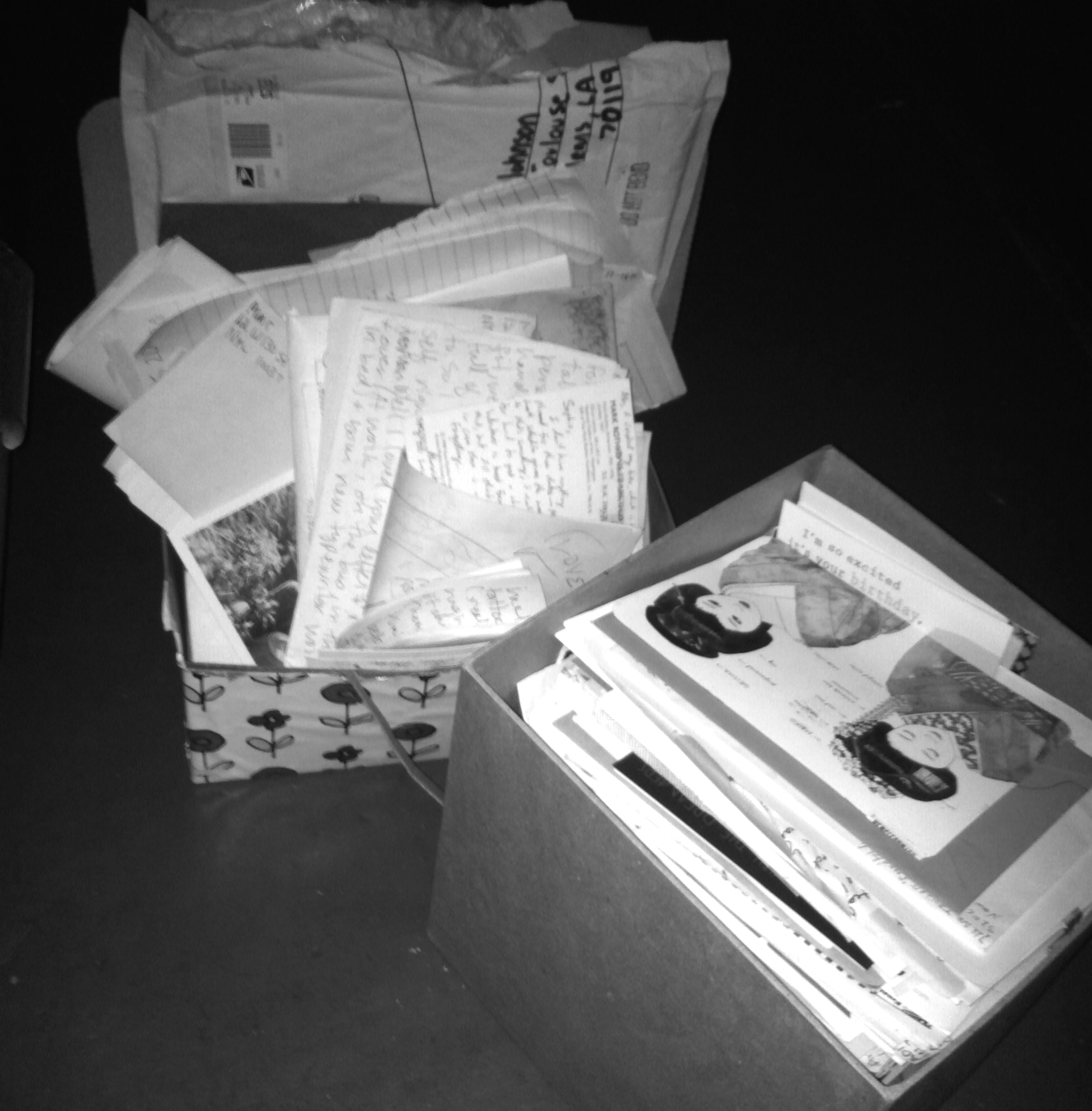

I have kept every letter I have received since I moved to New Orleans. They live in boxes under my big crafting table. Every so often I dig my fingers into the boxes the way Amelie did with the sacks of grain in that movie -- just to touch something that brings me joy to touch. Sometimes I dig letters out out and read just a few sentences: "That sundrenched feeling calls. And Kate will be the perfect shield from the drama-loving life-sucking group of immature fucks I know are waiting to pounce on me, because she couldn't give a fuck about any of them;" "Just spent a long weekend with my family. A little disturbed by how unfamiliar we felt. The subway and architecture and Dominican women are my favorite parts of the city so far;" "I actually went into that pub before I came here and asked if they had food. When the bartender said no, an old guy sitting at the bar offered a 'crisp,' to 'hold me over.' Students are walking home from school and someone just ROLLERBLADED by me."

The best ones do not commemorate occasions (like birthdays or graduation). The best ones are not about me. The best ones are the ones that mark small moments in time, that tell little stories that would otherwise be lost. I forget having read them, and I read them again, and every time they come alive.

I will continue sending letters, even after stamps cost ten dollars a piece. So long as I can scrawl out some long-winded idea or dream, throw it in a box, and know that it will appear somewhere far away from me, I will write them. To insist (perhaps futilely, who knows) on markers to hold my life to. To hold in my hands the loves that have defined my time.