Your Work Isn't Good Enough

I spent all my free time last week writing a reflection about my year for my blog. A reflection is a yearly tradition of mine that I started my senior year of college, and kept going after the Teaching Program Which Shall Not Be Named* recommended its teachers write one at the end of the school year. In years past, the reflection has not taken “all of my free time last week.” Writing it typically takes an hour; maybe two. But this year I sat writing, listing, deleting, pacing, obsessively drawing, and feeling generally unable to deliver a piece of decent writing. After it was done I told Luke, “I feel like I just gave birth, and I don’t even like the baby."

I posted the reflection cautiously, feeling embarrassed. Re-reading the sections I didn’t cut (probably 2,000 words ended up being cut, because they were all too syrupy and sentimental and irrelevant, etc.), I found myself annoyed with the person who wrote them. I hated my overuse of adverbs. The parts of the reflection that were meant to be funny came off as saccharine and cute; the parts that were meant to be serious were unreadable. Last year, I wrote about my cats and enjoyed every minute of it. I liked writing it so much I essentially wrote a second reflection a week later about leaving New Orleans. After a single year in a graduate level writing program, I had lost my will — and, I thought, my ability — to write.

Last year I started to see some success with my writing. The first time it happened I thought, Well isn’t this a lovely fluke! Some kind of kismet has caused some up-high editor to be, strangely, interested in my work. And then it happened a few more times, and by December I thought, I am an unstoppable machine. Everything I write is marketable gold. The way I started to think about writing changed. Instead of thinking, “What do I want to write about today?” I thought, “What does Publication X want to publish?"

At the very end of the year, a piece I’d had accepted at a big website was restructured to a point that I no longer felt myself reflected in it. I said the changes didn’t work for me; the article was cut. No big deal, I thought.

Then a piece I toiled over specifically for another site was not just rejected, but flat-out ignored. The next one was rejected by six different publications that had previously been interested in my work. The next five essays went nowhere; no one wanted them. I’d spent hours on the phone interviewing people about their deepest and darkest thoughts for some of the essays, hoping to hone my reporting skills. Those disappeared into the ether of unwanted submissions, too.

My most recent rejection said, “This is bland and heavy-handed. Where is your voice?”

You hear about this happening all the time to other people: They sell a book or make a great album or post a viral video, and they can’t replicate it the second time around. This is such a cliche that there’s a term for it: the feared-but-inevitable sophomore slump. After selling a gazillion copies (somehow) of “Eat, Pray, Love,” Elizabeth Gilbert did a Ted talk about how horrible it was to be in the position of having just made something noteworthy:

Everywhere I go now, people treat me like I'm doomed. Seriously -- doomed, doomed! Like, they come up to me now, all worried, and they say, "Aren't you afraid you're never going to be able to top that?Aren't you afraid you're going to keep writing for your whole life and you're never again going to create a book that anybody in the world cares about at all, ever again?"

Just to be clear, “Eat, Pray, Love” was not only a book I never read, it was a movie I started watching ‘cause someone else wanted to, but turned off ten minutes in. I’m obviously too cool to like “Eat, Pray, Love.” That said, Elizabeth Gilbert says some very intelligent things about the creative process. The only thing that bugs me about the way she talks about this stuff is how she acts like it has always been easy for her to see that rejection doesn’t really matter; that writing is not about success. There’s no way she (or anyone) is 100 percent immune to the pleasant lure of other people’s favorable opinions.

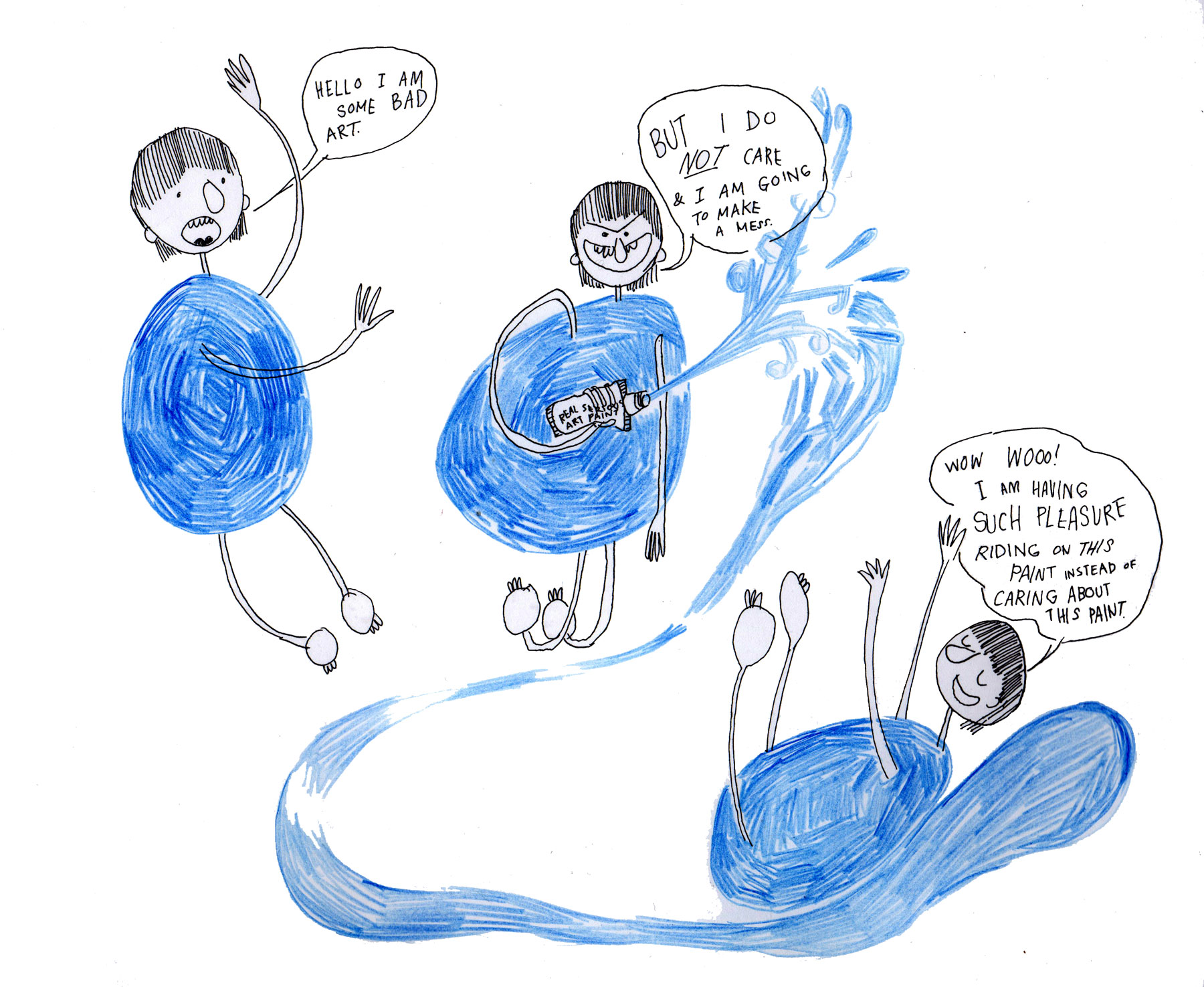

On Memorial Day, I went on a stroll with a writer friend and talked about my fear — I’m going with the word “fear,” because my recent inability to produce not only anything good, but anything at all, is almost certainly rooted in fear. She said that yes, she related: She had faced a similar roadblock in the winter when she wrote something she "actually liked.” After that, she got into the problematic habit of starting and deleting and starting and deleting, hoping to find the invisible stuff-she-liked key; which is a little like trying to find Narnia. She told me that she had been advised to “write crap” for as long as it took. “Write it and stick it in a drawer and then write more crap.”

And then yesterday I had to go to the school newspaper office and say which articles I thought were the best ones published all year so that we could submit them to contests. I have always hated this kind of activity. I run a small literary magazine and if there weren’t other people there to read the submissions and tell me to reject some of them, I would accept them all. Who am I to say what’s good and what’s bad? I really think it’s subjective. And in fact, this whole good-bad hierarchy limits the scope of what art can do.

So I can’t honestly decide that this article about Israel is “better” than this article about how Patti Smith saved someone’s soul. Both are great; both are exactly what they needed to be at their moment of inception and completion. This is so obvious to me. It is much easier understand the truth when it concerns someone else.

People will try to give you all kinds of reasons to be interested in the marketability of your work. “Don’t you want your work to reach as many people as possible?” “If you really want to make change in the world, you can’t do it privately.” “The prospect of success will push you to get better.” “This is the only way to make a living off what you love.”

To these arguments I say: Fuck "making a living" off what I love; fuck “getting better.” I am not going to produce work at all if I don’t enjoy making it — I’ll end up typing and deleting and typing and deleting, while muttering to myself, “IS THIS MARKETABLE!?!?!". I think you can tell when someone doesn’t enjoy making something. There is a dryness; a lack of honesty. I am deliberately not going to believe in such a thing as “better,” knowing fundamentally that practice will guide the work in whatever direction it is meant to go. People who are constantly making plans about how and when they ought to practice, or analyzing the ways in which they practice, are the people who end up not practicing at all.

* We’ll say it rhymes with “Preach for A Rare Licka.”